I always go back to the Silverstone circuit with a bit of nostalgia. It was on that circuit that I made my debut back in 1977 as a journalist. It was a historic race because that same year the British Grand Prix had abandoned its usual location on the Isle of Man.

It was a revolution to abandon the legendary Tourist Trophy with its 60.721 km circuit between low walls, pavements, lamp posts and crags. The TT had been held since 1949 and for the British it was a tradition that has survived to this day, albeit without any championship validity.

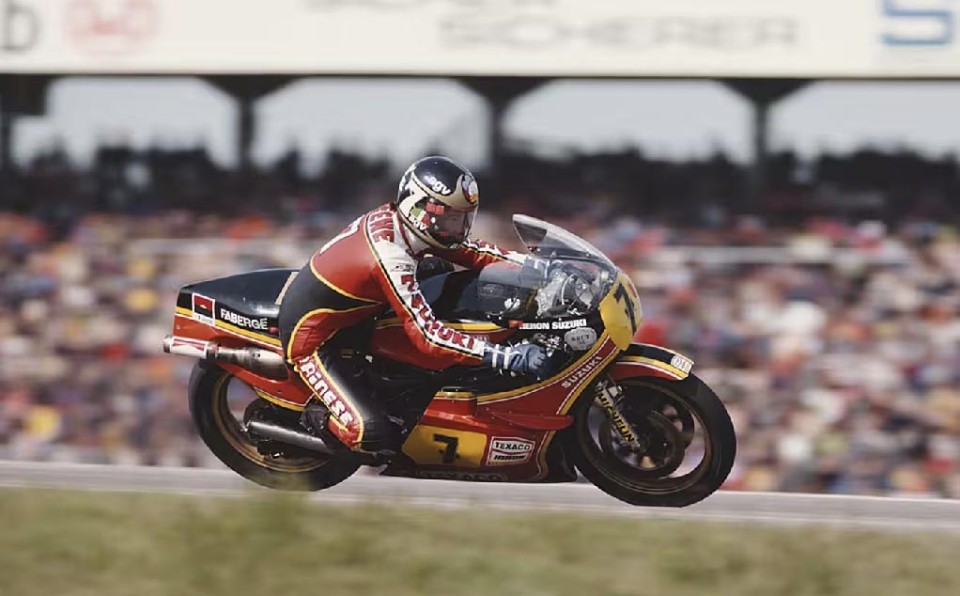

The best riders of the time took action to bring an end to the legend of the Mountain: Giacomo Agostini, still saddened by the loss of his friend Gilberto Parlotti in 1972, the Spanish Federation, which denied authorization to compete after the death of Santiago Herrero, rising Hispanic star with his single-cylinder Ossa, in 1976 but also and above all many British champions. Barry Sheene, one of the fiercest opponents, Rodney Gould and also Phil Read, who then went back later.

Was that a breakthrough year for safety? Not at all. In 1977 the world championship raced at Salzburg, a deadly circuit, on the super-fast Hockenheim going through the woods that caused repeated seizures, at the old chicane-less Imola, and then at Spa-Francorchamps where in 1977 Barry Sheene set the highest average race speed ever, 217.37 km/h, winning the Belgian Grand Prix on the 14.12 km circuit. and on the Imatra road circuit, even there among pavements, lamp posts, trees… and railway crossings.

Salzburg survived the following year and also Spa, Imatra and even the old Nurburgring. So what are we on about? It was another era and just two year later there was a strike organized by Roberts, Sheene and Ferrari right at Francorchamps which made the International Motorcycle Federation and its President, Nicolas Rodil Del Valle tremble with the threat of the World Series: an alternative world championship.

It didn't, but the wind was changing. The riders were tired not only of the lack of safety that led to losses every year, but also of having to queue up to get their start money and having to recommend themselves to the organizers in order to take part in the races.

In that slightly bohemian atmosphere, I arrived at Silverstone at night, pitched my tent and in the morning I went to breakfast in an old central building in dark wood that served as a refectory: beans, sausages and fried eggs, of course! Green grass all around the circuit and, inside, a few, old, rather promiscuous toilets and showers. But in the days of long hair, flared trousers and flowered shirts, when Barry arrived at the circuit with George Harrison of the Beatles who cared?

In that 1977 there were still no motorhomes: the first ones were brought by Kenny Roberts the following year, a luxurious Sportscoach. Back then they were all caravans... for the lucky ones, because for many riders there was a tent.

There were six categories: 50, 125, 250, 350, 500 and sidecars, recognizable not only by the size but also by the colour of the number plate: who could confuse a MV 350 with a 500, with the first blue and the second yellow?

That year, 1977, the winner of the Grand Prix was not Sheene, who was beginning to be idolized by the public. Barry crashed, his brotherly friend Steve Parrish also crashed, and then John Williams. The win went to the American Pat Hennen, whose career was dramatically interrupted the following year due to his decision to race the TT which was not valid for the world championship. He survived, but stopped racing. Behind him Steve Baker and Tepi Lansivuori. Fourth was our very own Giancarlo Bonera, whom I remember fondly because on that occasion, as I approached him excitedly and playing around with my camera, he welcomed me with a caustic "amateurs in the deep end!".

There were - fortunately - no press officers. The relationship was one to one. There were some days you got a welcome hug, but the next day you might have picked up a ‘fuck off’ if you wrote something wrong. But always with that direct and never offensive approach, between equals. Because it was passion, then, that moved everything, not money, which very few earned.

Of course I regret that Silverstone, when the world championship was very poor, but very happy, despite the danger and a snooty and overbearing FIM. But the wind was about to change. The riders had become aware of their power, and then that genius would arrive, a very good person, a dreamer, the engineer Luigi Brenni to undermine the CCR - the road racing commission - and talk about safety, fair racing fees and so on.

We went on to have other accidents, even at Mugello which debuted in 1978 with virtually no run-off areas, but the way was outlined even if it took years. Until the arrival of Dorna in 1991, in the wake of Bernie Ecclestone and his Two Wheel Promotion. That British weasel had realised that for him, accustomed to F1, there was nothing doing there and he gladly gave it up. But most of it had actually been done, and every time I went to London I remember that in Piccadilly Circus there was a gigantic billboard with Barry Sheene promoting Fabergé aftershave, which I too tried, finding it sickeningly sweet. But, all things considered, it didn't clash with the flowered shirts.